- Charlotte D.

- Wednesday, June 21, 2023

For World Refugee Day on June 20th, here's the story of one long-time Columbia resident and refugee - who happens to be my dad.

My father never talks about his past. Whether it’s from his years of waking up screaming in the night, or because he’s always been a reserved man around his children, I’m not sure. What I have learned about his time in Vietnam, I have learned from my mother, who also woke up screaming when I was young, but who has remained vocal about her time, and my father’s time, in a war-torn country. And in recent months, my father has opened up about his time in Vietnam – perhaps due to fleeting time, perhaps as he and my mother have mellowed as they age.

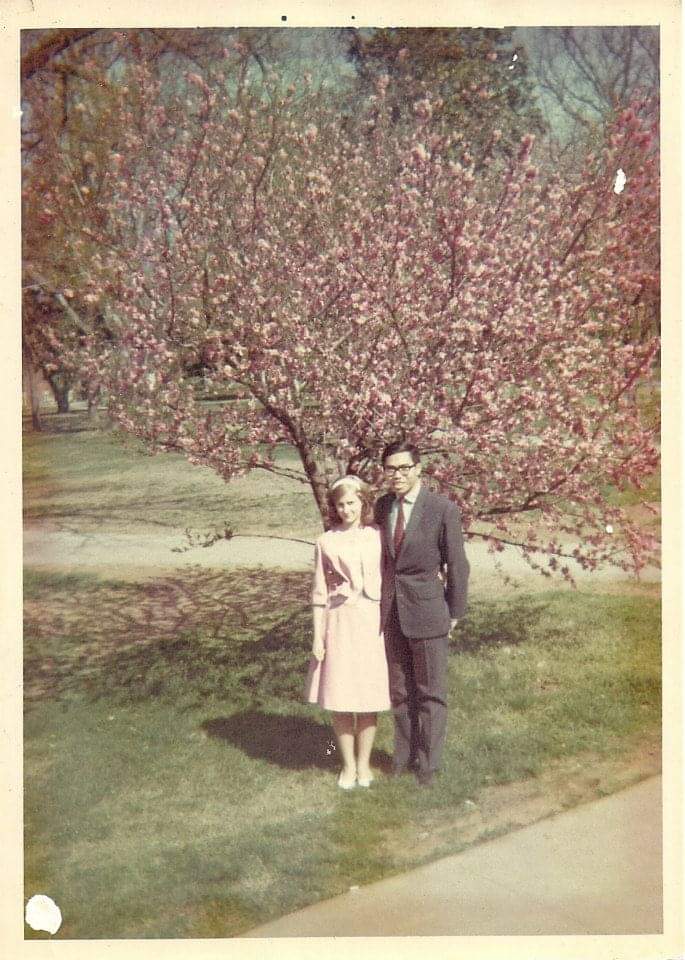

My parents met in 1965 at George Peabody College, which has now been absorbed by Vanderbilt University. My mother was a freshman, and my father was in graduate school pursuing his master’s in education after having earned two bachelor’s degrees in three years at the University of Saigon. They met at a mixer, where my father asked for the pleasure of the next dance. When he escorted her back to her dorm that evening, he asked if he might have the pleasure of escorting her to various events around campus. His smooth moves, as it turned out, were learned from a nineteenth-century French courtship book. They worked, though. My parents continued dating after my mother transferred to Memphis State University (now the University of Memphis) and my father went on to complete his doctorate at the University of Iowa. By 1969, they were engaged, and by 1970, my mother was moving to Saigon to marry my father and teach English literature at the American high school there.

My parents, once married, didn’t want to leave Vietnam. My grandfather, a prosperous merchant, had built a third-story apartment for them on top of the two-story family home, and my father was splitting his time teaching at the University of Saigon, the University of Hue, and the American high school where my mother taught. They planned to stay and take care of my grandparents as they aged. My parents wanted to raise their children in the family home, in their apartment they shared with their chihuahua, Gigi.

My mother would go home every summer to her parents’ home in Paris, Tennessee, while my father served in the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN). What he experienced there, and also guarding the University of Saigon during the school year, I may never know. He does not tell his children these things. My mother recalls seeing a man get executed for speeding in traffic during her first night in Saigon; she also remembers my father’s mother refusing to leave the bed the night the family home was raided by corrupt police officers because a small fortune’s worth of gold bars was buried beneath the floor. An elementary school on my parents’ street was bombed during the war; so was a monastery a few blocks away. These events alone left my mother with PTSD symptoms that still haunt her. My father, who remembers hiding in the central highlands of Vietnam during the Japanese invasion, does not regale me with such stories.

But when my mother left on her summer breaks, or when my father left for business trips, the remaining spouse was forced to stay in Saigon. My father’s dissertation was published by the American Statistical Association in 1970 and was the basis of the Huynh-Feldt statistical correction and theorem, a modern standard of large-scale assessment and statistics. He was the only person in Vietnam with a degree in educational assessment and was considered a valuable asset to the South Vietnamese government. The government figured that as long as they held my mother or father back in South Vietnam, the other would come back. This was another reason why they stayed in Saigon.

Refugees, no matter their education or status, are people: they laugh, they cry, they bleed, they breathe.

By 1973, though, circumstances had changed. Political chaos had erupted, and my mother was several months pregnant with my older brother, Michael. If my parents stayed in South Vietnam when my brother was born, he would be considered a Vietnamese citizen, and my parents would not be able to take him out of the country. My parents each applied with different government offices to leave the country, my mother for her summer vacation in Tennessee, my father for a summer research position at the University of Pittsburg. With the turmoil inflicted on the South Vietnamese government, the two offices never compared notes, and my parents made it successfully from Saigon, to Taipei and Tokyo, to San Francisco and Memphis, with no one realizing they were permanently fleeing their home.

After my father’s research visa ended, he applied for political asylum and was denied. He and my pregnant mother received the news that he would be sent back to South Vietnam, where he would surely await punishment. Senators Bill Brock and Howard Baker of Tennessee intervened on his behalf, and in December 1973, my parents welcomed my brother, Michael, into the world, with my father now established as a permanent alien resident of the United States.

The rest of my family did not fare as well. With the fall of Saigon in 1975, my oldest uncle, Ba, was imprisoned for six years in a re-education camp, punished for being a captain in the ARVN and the assistant to the chief of Gia Dinh province. Another uncle, Bay, was imprisoned for years as well, simply for being a math teacher at a local Saigon high school. One of my oldest cousins was sent to fight in Cambodia; his parents were informed of his death and burial in a mass grave two years later. My grandfather now couldn’t get insulin for his diabetes because he would not swear allegiance to the communist party. My parents, in Boston and then Columbia, South Carolina, sent valuable items to him to sell on the black market so he could get his medications. My father, as my mother tells me, could do little to help them get to the United States as he still wasn’t a citizen and my mother was not considered their immediate family. It baffled him, seeing as the Vietnamese have no concept of in-laws within family; in-laws are considered second family, just as important as the first.

As soon as my father became a citizen in the 1980s, he started the process of sponsoring family members so they could come to this country. Uncle Ba, who had emerged young but white-haired from the re-education camp, crossed the Killing Fields with his wife and two of his sons to reach a Thai refugee camp, where they contacted my father so he could sponsor them. One of my cousins was in a ship en route to a refugee camp when it was attacked by pirates; he survived and made it to the States. Other family members soon came, all sponsored by my father, and spread throughout the country: California, Massachusetts, Texas, and South Carolina. My family has prospered here. They are pharmacists, small business owners, and software engineers. They are now United States citizens; they pay their taxes; they pursue higher education; they care for their families.

But I don’t want to emphasize the idea of exceptionalism. The model minority myth remains a dangerous and harmful one. Refugees, no matter their education or status, are people: they laugh, they cry, they bleed, they breathe. They are my family, my neighbors, and my friends. What would have happened if the senators from Tennessee had not intervened for my father and he was sent back to Vietnam? My mother would have raised my brother without my father’s support, and my sister and I never would have been born. What would have happened if my Uncle Ba and his immediate family had gotten to the refugee camp and not had a sponsor? They would have been turned away and been left to the Khmer Rouge soldiers at the Cambodian border.

They live, they breathe, they hope. My family fled danger in pursuit of a better life for their children and themselves - not because they wanted an easy way out, but because they had no other choice. I will continue to tell my parents’ and my family’s story as long as I can, not because my family is exceptional (though I believe they are), but because these stories are far more ordinary than many would believe.

The Mediterranean

No Friend but the Mountains

Out of Many, One

Tehran Children

Those We Throw Away Are Diamonds

The Kitchen Without Borders

After the Last Border

Beyond the Sand and Sea

This Land is Our Land

The Ungrateful Refugee

The Lightless Sky

Outcasts United

A previous version of this piece was published by Unsweetened Magazine in 2017.

For more information about the United Nations and World Refugee Day, click here.