- Margaret D.

- Friday, September 15, 2023

For Hispanic Heritage Month, I took a look at a little-known chapter of history that unfolded in Columbia at Fort Jackson, where several thousand Cubans came to receive military training and United States citizenship.

In 1963 with tensions high between President John F. Kennedy and Prime Minister Fidel Castro of Cuba, an experimental program invited Cubans to enlist in the U.S. Army with the promise of U.S. citizenship granted at the completion of a successful training program.

October 1962, Cuban Missile Crisis

Just months earlier in October 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis had culminated in a 13-day stand-off between the USSR and the United States over Russian nuclear warheads in Cuba. This event, which some believed nearly led to nuclear war, strengthened American resolve to support Cuban refugees opposed to Castro’s communist regime.

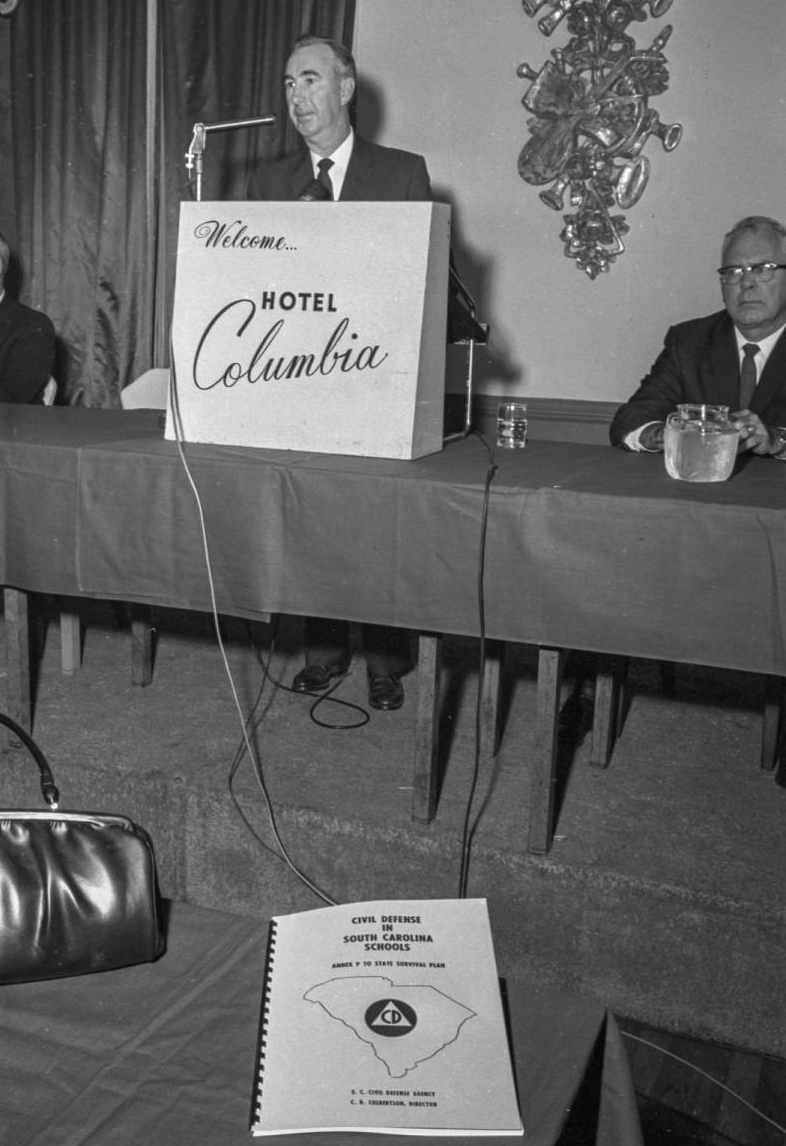

Civil Defense planners held tense meetings in Columbia during the Cuban Missile Crisis to discuss how to prepare for a nuclear attack. So, no doubt the locals were happy to welcome Cuban exiles opposed to Castro's government into our community. At this time during the Cold War, the United States, Great Britain, and other western nations were keenly interested in stopping the global spread of communism. A stance that would eventually lead to the Vietnam War.

January 1963, Cuban Enlistees Arrive

On January 5, 1963, a group of 900 Cubans arrived at Fort Jackson to participate in a novel military training program. Photographs in our library collections show an enthusiastic group of young men, all smiles and full of energy.

Just 5 days after their arrival the trainees were being shown off to visiting British Secretary of War John D. Profumo and his entourage. During his tour of the Fort with Commander Major General Charles S. D’Orsa, Secretary Profumo observed the Cuban trainees firing M-1 rifles at the Fort’s firing range. When asked about President Kennedy’s response to the Cuban Missile Crisis, Secretary Profumo replied that the British government felt Kennedy’s “recent firm stand has strengthened greatly the West’s position.”

Cuban paramilitary forces had in fact been supported by the CIA to combat Castro in Cuba since 1961. But the Cuban training battalions at Fort Jackson were part of the U.S Army and being trained in Columbia amongst the other American enlistees. Unlike many other trainees at Fort Jackson, the Cubans were acclimated to Columbia’s heat. In fact, they had been reassigned to Columbia after finding the weather too cold in Ft. Knox, Kentucky. But time would show that there were other hardships the Cubans would experience here.

At its inception the Cuban Volunteer Training Program, as it was called, comprised of 22 weeks of military training in Spanish under bilingual officers under commander Lt. Col. Paul R. Kennedy. Graduates of the program were asked to take an oath of allegiance to the United States and were granted citizenship. Fort Jackson’s Commander Maj. Gen. D’Orso welcomed the first group in Spanish and Spanish-language signs were placed around the base. In the first 6-months 1,473 trainees had graduated from the program.

June 1963, Conditions Change

But, by June 1963 the United States had pivoted to taking a new “neutral” strategy with Cuba, and training Cuban exiles to combat communism in Latin America was not part of the new plan. The bilingual officers that worked with the Cubans were moved to other posts and English-speaking commanders were put in their place. What were at first Spanish-speaking battalions became integrated with American troops and English was now the only language in use. The Spanish-language signs came down.

With the conditions altered so significantly for the Cuban trainees, there was mistrust and confusion between the Cubans and their officers. When a Cuban trainee struck an officer, the Pentagon got involved and Senator Strom Thurmond investigated the incident and alerted local media.

In August 1963 the Cuban Volunteer Training Program ended abruptly. Mistrust and confusion, changing military strategy, and public sentiment all played a role in the discontinuation of the program. Maj. Gen. D’Orsa complained that the program was a failure due to the constant rumor-mill surrounding the Cuban trainees, with Sen. Thurmond taking the last jab by alerting the media to the fight on base. Gen. D’Orsa, an Italian immigrant himself, was frustrated by constant suspicion that Cuban trainees were somehow receiving preferential treatment over American trainees. Of the Cubans, Gen. D’Orsa said, “They are good soldiers, and they received the same treatment as American troops.” (The State, August 16, 1963).

Outcomes

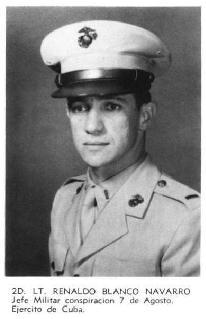

In the end, over 3,000 Cubans completed the program. According to enlistee and Bay of Pigs veteran Pvt. Nelson Blanco-Navarro, some military-trained Cuban exiles like his brother, Renaldo (pictured below), went on to hold posts in the United States military. Others held civilian jobs in the United States, waiting for word when they might be needed to support the United States’ interests in Cuba. Blanco-Navarro wanted to eventually return to a liberated Cuba and had hoped that his US military training would allow him to help in that cause.

This brief program brought many new citizens to America and provided the military with experience in training enlistees in a language other than English. It also highlighted the cost of rumors and suspicion in missed opportunities. It is an American story, with its highs and lows, after all.

To learn more, check out the articles I found on the topic through the library’s NewsBank database.

Local newspaper sources:

- “900 Cuban Expatriates arrive at Fort Jackson,” The State, January 6, 1963 p1A.

- “British War Minister visits Fort Jackson,” Columbia Record, January 10, 1963 page 1A.

- “British government is well-satisfied with the swap of Skybolt for Polaris,” The State, January 11, 1963 page D1.

- “Cuban, American troops will mix,” Columbia Record, June 4, 1963 page 8B.

- “Cuban trainee strikes officer at Fort Jackson,” Columbia Record, June 25, 1963 page A1.

- “Fort writes end to Cuban story,” The State, August 16, 1963 page A1.